A short essay of mine over at Bella Caledonia called Unwilding Scotland attracted many intelligent responses. It’s taken me too long to reply but I thought I’d try and clarify a few things.

Since I first wrote on this topic a few months ago (again at Bella) the debate seems to have acquired a renewed energy. I find this reassuring.

What follows is mostly in response to Paul Webster’s comments (Paul runs the wonderful Walk Highlands website which is more or less essential browsing for anyone planning a longer walk in Scotland).

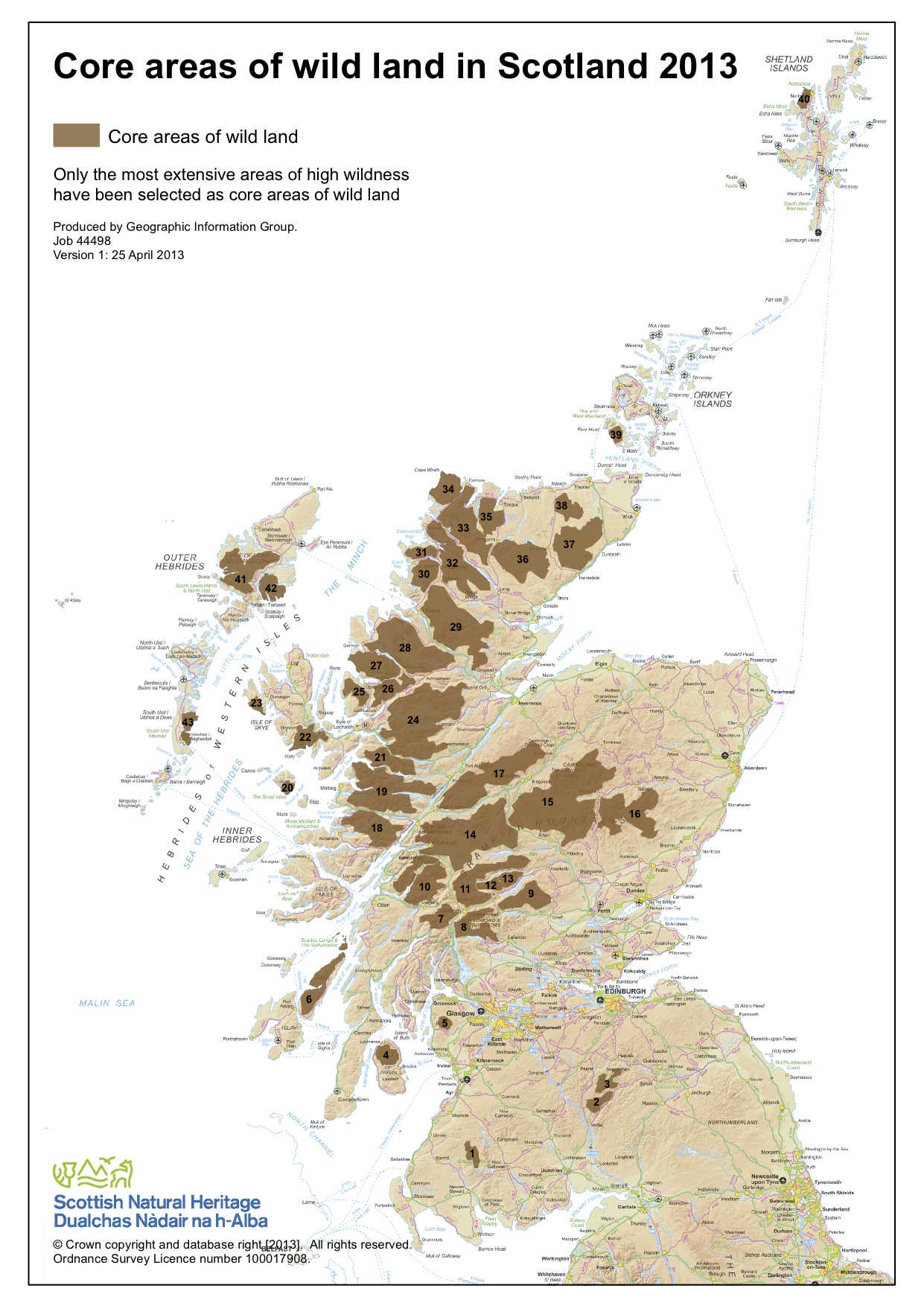

Paul has a fair point when he complains that when I talk about the Uist machair, I don’t make it sufficiently clear that this doesn’t lie within any of the SNH proposed areas of ‘core wild land’. This wasn’t intentional obfuscation on my part. My experience of living in North Uist certainly informed my thinking about how much labour goes in to making Scotland’s landscapes conform more closely to the aesthetic ideals that are projected on to them.

My key point is this: areas of ‘core wild land’ may not include the machair land but the hills are still very much part of the cultural hinterland of the more inhabited districts. Part of the abstracting philosophical consequence of ‘wildness’ is to separate such landscapes from the very people who have the greatest cultural claim on them.

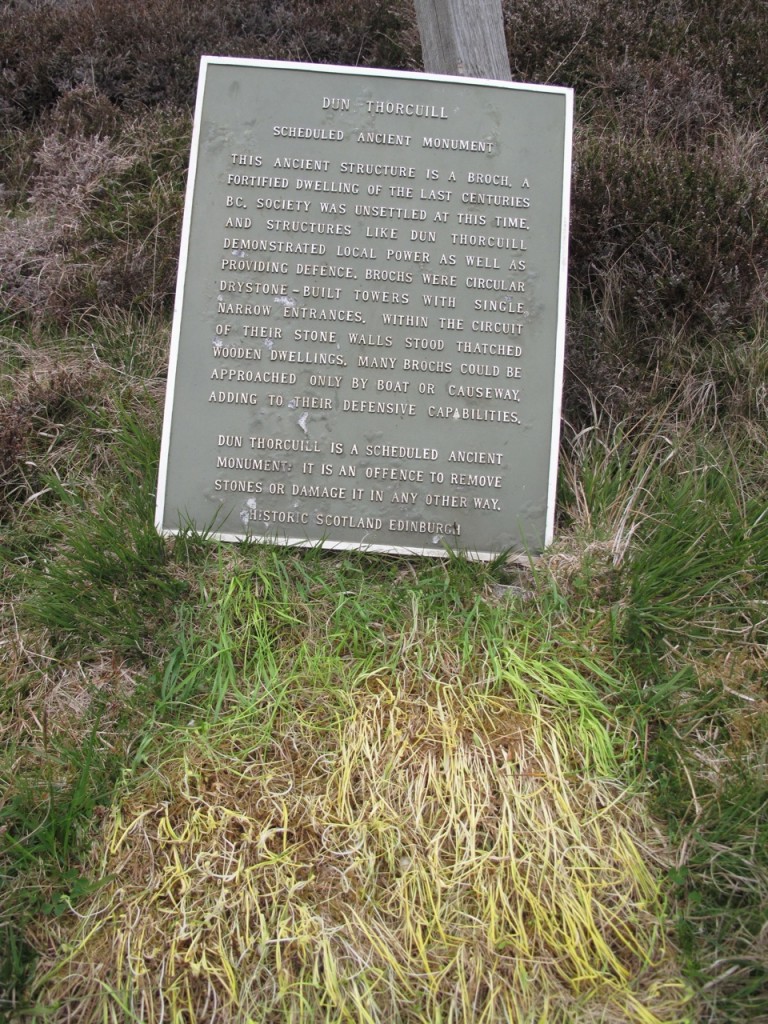

The hill land of South Uist – ‘core wild land’ for SNH – is not a place set apart, a landscape that can be meaningfully detached from the islanders on the west side. Unfortunately that, as I see it, is the rhetorical function of wildness as it being used here. Just because a place is not currently inhabited does not mean that it is some kind of tabula rasa to be reduced to its visual attributes for the passing hillwalker.

There are doubtless ‘wild’ places in Scotland that are less tied into their hinterlands than is the case in South Uist. But that merely reveals that the concept of ‘wildness’ is entirely insensitive to local cultural nuance.

The Uibhisteachs, to my mind, are right to be worried. They should be concerned that such a move may inhibit their ability to use the land resources that have been so hard won. There is also a wider argument to be made about the continuing failure by the state-sanctioned guardians of our natural heritage to recognise and celebrate the ways in which our natural history and cultural history are entwined.

The language of wildness always tries to keep these at arm’s length. In their consultation paper, SNH say that ‘the evidence of past and contemporary uses of these areas is relatively light, and do not detract significantly from the quality of wildness’. Detract significantly? Can’t we just stop conceiving the presence of people – historic or otherwise – as some kind of loss?

Why not think of human activity as being a constituent part of what makes these areas interesting and meaningful?

Wildness ties us up in knots. It requires all sorts of qualifications and clarifications on the part of the conservationists: ‘yes, we know that it isn’t really wild…’; ‘light evidence of people may not be too bad …’ etc.

It simply isn’t a useful term to carry a richer sense of landscape as being a hybrid labour between humans and non-humans.

I don’t for a moment think that SNH want to impose the attributes of wildness on the whole of Scotland. Rather, my problem is that they want to fix ‘wildness’ (and its proxies) as being the defining aesthetic for a big portion of the Scottish landscape. It’s an aesthetic ideal that carries some hefty political baggage and has no democratic mandate in the very regions that are deemed most wild.

One of the problems that besets the whole debate is that proponents of ‘wildness’ can’t see past the category itself. We need to understand wildness as itself a way of seeing rather as some external reality ‘out there’ in the hills.

So statements like this from SNH are rather trying:

“The appreciation of wildness is a matter of an individual’s experience, and their perceptions of and preferences for landscapes of this kind. Wildness cannot be captured and measured, but it can be experienced and interpreted by people in many different ways.”

In other words, you can have any flavour of wildness you like as long as it’s wild. Great. There doesn’t seem much room here for the many people for whom wildness is simply not the cultural lens with which they see the Highland landscape.

The argument that wildness is what brings tourists to the Highlands makes the same mistake of failing to see past the category. We must not conflate the Highland landscape with the cultural lens of wildness. Yes, ‘wildness’ is one part of how the Scottish Highlands have been iconographically represented (though the same taste for wildness didn’t always have happy consequences on the ground).

But this is less an argument about what Scotland should look like and what sort of nature we might want, than it is about how we should conceive of Scotland’s landscapes. That distinction is crucial and, at the moment, it’s mostly forgotten.

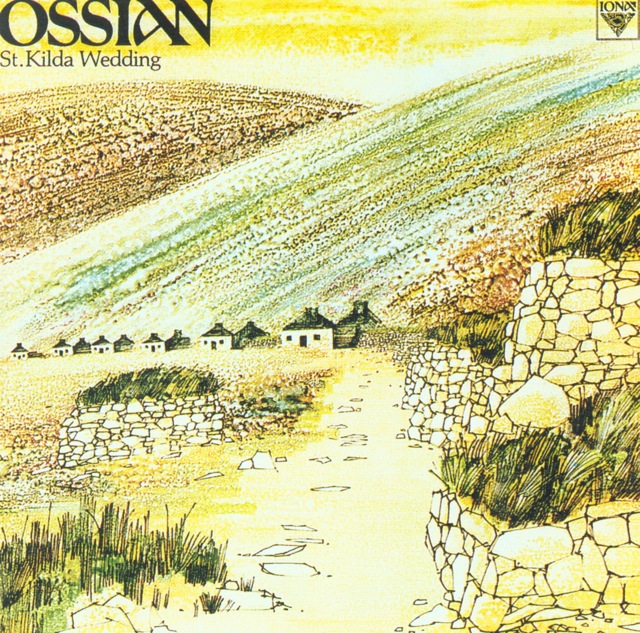

The built environment might have been equally striking had countless images of this abandoned village not already been intimately known to me since childhood.

The built environment might have been equally striking had countless images of this abandoned village not already been intimately known to me since childhood.

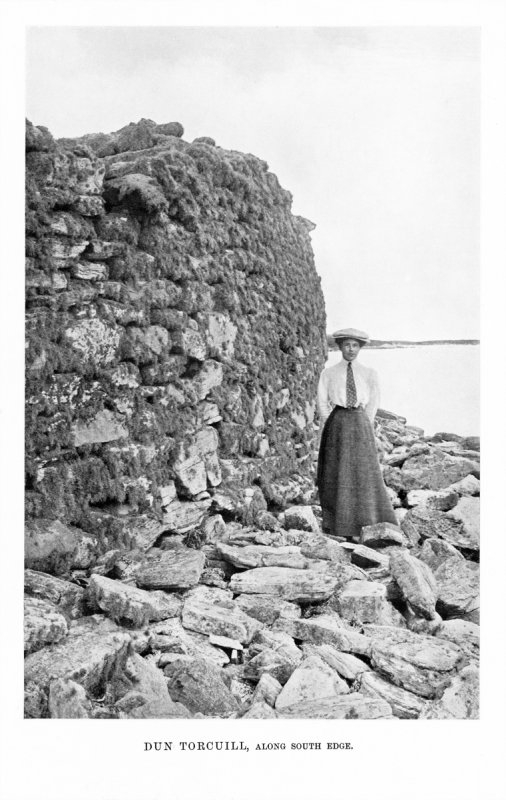

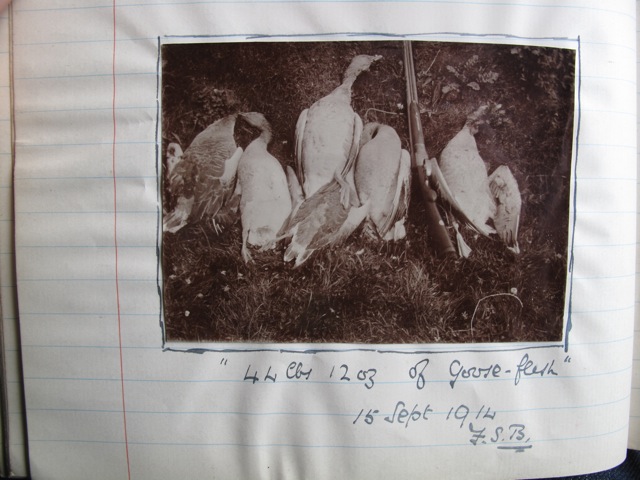

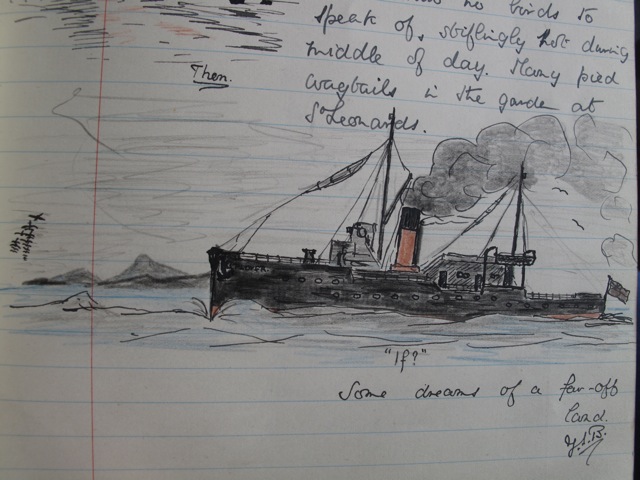

It was more lightly encrusted when the antiquarian Erskine Beveridge (1851-1920) visited in the early twentieth century. This is his photo of the site.

It was more lightly encrusted when the antiquarian Erskine Beveridge (1851-1920) visited in the early twentieth century. This is his photo of the site.