There are certain places that prove quite irresistible. We can find ourselves under a compulsion to know or inhabit or encircle a particular site.

I am enlivened by one such place; I pass it daily and often feel its pull. It is an unlikely spot: the Istanbul kebab shop at 80 Portobello High Street.

Some time ago this building was known by a different address, by a different appearance and for the renown of its celebrated occupant, whose name is no longer met with universal recognition.

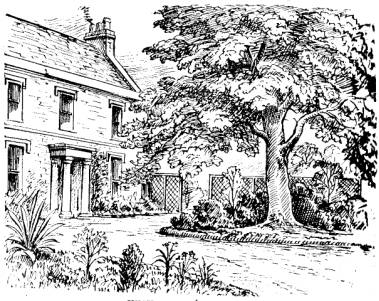

‘Shrub Mount’, as Istanbul was then called, was the Portobello home of the eminent Victorian geologist, editor and writer Hugh Miller.

It was to this building he escaped from the stresses of editing a national newspaper, The Witness – it then outsold The Scotsman – and where he retreated to study in the private museum he had built in the grounds of a once extensive garden.

The bounds of this property are now unwittingly marked by the daily ebb of parents discharging their children at the adjacent Towerbank Primary School. These ordinary residential streets give little indication of the histories that precede them.

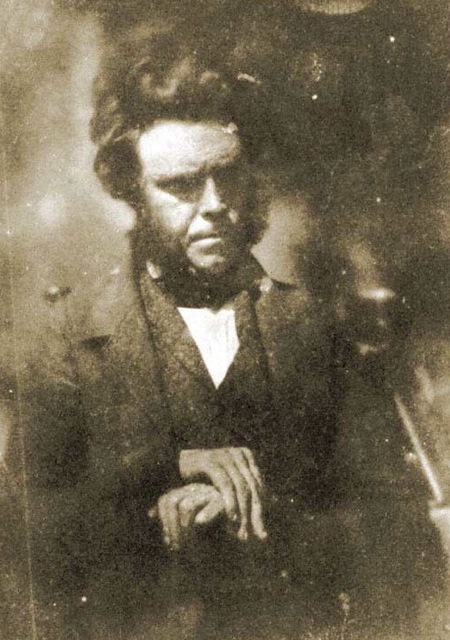

Hugh Miller was one of the most important figures in nineteenth century science. A correspondent of the preeminent scientific figures of his day, from Louis Agassiz to Charles Darwin, he was also a leading proponent of the ecclesiastical Disruption that saw the formation of the Free Church of Scotland in 1843.

In his Edinburgh life, he was close to the other Disruption ‘worthies’ – Thomas Chalmers, William Cunningham and James Begg – at a time when the young Free Church was brimful of intellectuals.

Miller, however, never quite fitted in with either his scientific or ecclesiastical contemporaries. He didn’t look like them, nor did he sound like them. He eschewed urban fashions for the heavy woollen plaid, a knowing self-presentation as the outsider that was famously captured in the stills of David Octavius Hill.

Steeped in the folklore and superstitions of his native Cromarty, Miller had left school at 14 to become an itinerant stonemason and had educated himself through reading, corresponding and by closely observing ‘the testimony of the rocks’.

His rise from wayfaring workman to scientific luminary, brilliantly narrated in his bildungsroman memoir My Schools and Schoolmasters, is a canonical story of nineteenth century Scotland.

Miller’s modest origins in combination with his forthright politics meant he was often rejected by the scientific establishment. The University of Edinburgh, for instance, turned him down for the Chair in Natural History – a position for which he was more than qualified.

Hugh Miller was subject to depressive episodes and periodic ill health throughout his life. In the spring of 1839, his beloved daughter, Eliza, died aged two. For this firstborn child, he made his last work of masonry – a headstone for her grave in the kirk of St Regulus, Cromarty.

There is a page about Eliza’s death in My Schools and Schoolmasters where Miller does not give her name but writes only of ‘a little girl’. Thereafter, she becomes ‘it’: ‘it had left us for ever, and its fair face and silken hair lay in darkness amid the clods of the churchyard’.

In bereavement, even a pronoun can be too personal. Still reeling from this loss, the family relocated to Edinburgh.

In time, the exchange of Marchmont and Jock’s Lodge for the seaside village of Portobello might have been something of a relief. In any case, Edinburgh’s east was already familiar to Miller from a spell of masonry work on Niddrie Marischal House twenty years earlier.

Demolished by the council in the 1930s to re-house families of slum clearance, Niddrie Marischal House was the seat of the Wauchope family. It is now one of the more deprived places in Scotland.

Here the young Hugh Miller fashioned stone mullions for the windows of the big house. In the shadow of this same house he had also witnessed at first hand the widespread poverty of the Scottish colliers, some of whom, upon birth, had become the private property of the Wauchopes.

At Niddrie Mill, he described a ‘wretched assemblage of dingy, low-roofed, tile-covered hovels’, the occupants of which were ‘a rude and ignorant race of men, that still bore about them the soil and stain of recent slavery’.

This is classic Miller. Though he could recognise well enough the brutality of the system that produced such misery, it rarely softened his judgement of those thus emmiserated.

When Hugh Miller returned to Edinburgh in 1840 as the archetypal self-made man he had no desire to proclaim his ascent into respectability. Shrub Mount was, to be sure, no Niddrie Marischal.

He sought a quiet life, at a distance from his peers in science and religion.

He worked. This meant writing, walking and reading the landscape.

I imagine that being in Portobello would have been a welcome reminder of his beloved Cromarty, both being situated on the south side of grand eastern Firths. Miller could take his four children down to the beach; or fossil-hunting among the rocks at Joppa; or guddling for invertebrates in the Figgate burn.

Guddling was always purposeful. By such means, Miller worked out that the red clays of the Figgie burn – famed for the production of Portobello bricks – ‘must have been slowly deposited in comparatively tranquil waters’.

At an exposure from a local brick works – a site near the old Roman road of the Fishwives’ Causeway – Miller found a bed of ancient shells. Though a long way inland, these were identified as Scrobicularia piperata, a distinctly intertidal species.

There was no mistaking the force of such evidence: the coastline had retreated. This land was once sea. Edinburgh itself had to be re-imagined:

We are first presented with a scene of islands – the hills which overlook the Scottish capital, or on which it is built – half sunk in a glacial sea. A powerful current from the west, occasionally charged with icebergs, sweeps past them … and in the sheltered tract of sea to the east of the islets, amid slowly revolving eddies, the sediment is cast slowly down, layer after layer, the brick clays are formed along the bottom.

One can only suppose that an unveiling of this magnitude, one not always welcomed by his co-religionists, might have proved exhausting. Miller’s life and death have all too often been interpreted as a simple tension between a commitment to Biblical inerrantism on the one hand, and empirical science on the other – with the vexed question of evolution in the middle.

This is why – so the popular version goes – that one Christmas Eve, in his upper room at Shrub Mount, Hugh Miller scribbled a note to wife, lifted his fisherman’s jersey and shot himself through the heart.

Miller’s suicide cannot be so readily explained. A fuller account might point to his failing health, overwork or domestic unhappiness. It’s complicated; and ultimately unknowable.

It is fair to say that at the end he was haunted by the apparent gap between the natural and the supernatural, between mystery and revelation.

‘Last night I felt as if I had been ridden by a witch for fifty miles’ he told his doctor, ‘and rose far more wearied in mind and body than when I lay down’.

So convinced that he had been involuntarily abroad in the night, that he would check his clothing for signs of the journey.

All of this was, for those left behind, a reassuring mark of insanity – such was needed to exonerate the sin of suicide.

And then there is his desperate suicide note:

Dearest Lydia

My brain burns. I must have walked; and a fearful dream rises upon me. I cannot bear the horrible thought. God and Father of the Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy upon me. Dearest Lydia, dear children, farewell. My brain burns as the recollection grows. My dear, dear wife, farewell.

Hugh Miller

All of this happened in a room above Istanbul. And I feel the gravitational pull of this site, this centre of geo-logic calculation: a modest retreat for thinking, for reading and writing, for arranging the long history of the Earth, for life and love and family.

It is his life, not his death, that moves me.