Memory practices and the national inventory of Scotland

FULLY-FUNDED AHRC PhD STUDENTSHIP

UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH

(Geography, School of GeoSciences)

Applications are invited for an AHRC-funded PhD, a Collaborative Doctoral Award (CDA), supervised jointly by the University of Edinburgh (Geography, School of GeoSciences) and the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS). The CDA Studentship is one of four made within the Scottish Cultural Heritage Consortium, which will provide an enhanced programme of student training.

The studentship is for a PhD on the theme of ‘Memory practices and the national inventory of Scotland’ which will examine the origins, personnel and activities behind the foundation of RCAHMS. The project will be supervised by Dr. Fraser MacDonald and Professor Charles W J Withers (University of Edinburgh) and Lesley Ferguson (Head of Collections at RCAHMS). The studentship is funded for three years full time equivalent and will begin in September 2013.

The Studentship

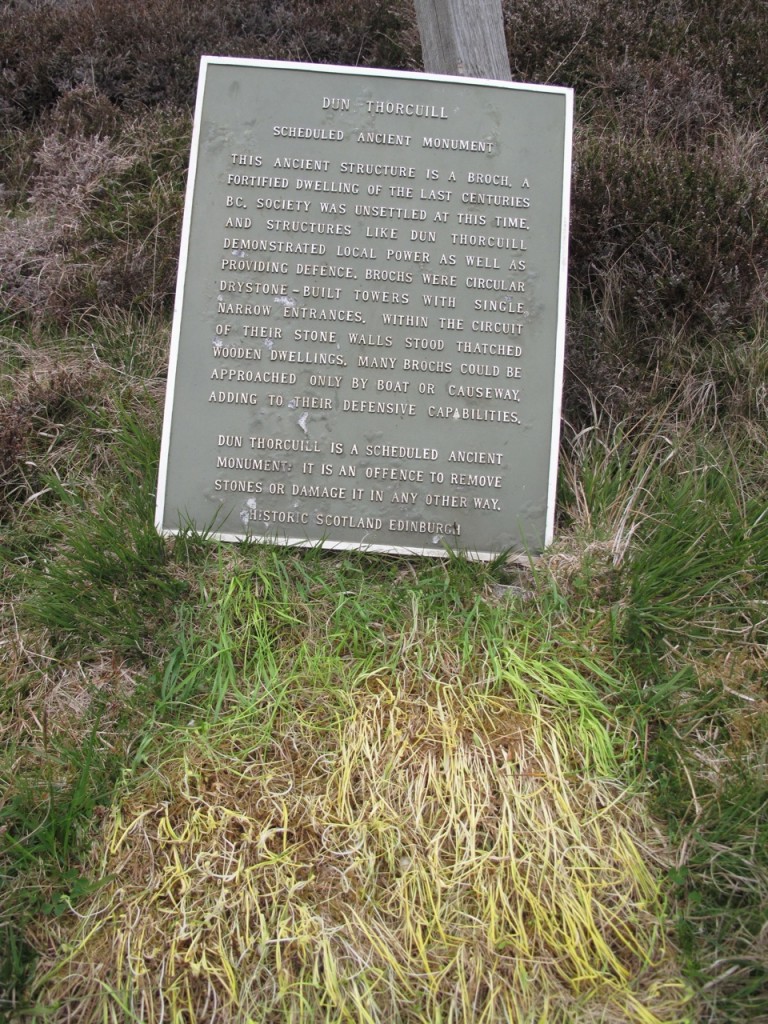

The project will use the archives and collections of RCAHMS to consider how our knowledge of Scotland’s material past has been developed through the work of ‘amateur’ scholars such as Henry Dryden (1818-1899) and Erskine Beveridge (1851-1920). It will explore how our knowledge of Scotland’s antiquities became professionalised and institutionalised in the early twentieth century. An important context to the project is the founding of RCAHMS in 1908 as part of a wider bid to create an inventory of surviving material heritage in Scotland, an aim that is set to continue with the creation a new body soon to succeed RCAHMS and Historic Scotland. Against this background, the studentship will examine the ‘memory practices’ – the activities, technologies and forms that scholars have used to record the past. The PhD will examine how it is that we have come to our present knowledge of the historic environment. It will do so drawing on literatures in historical geography, history of science (particularly archaeology) and architectural history.

How to Apply: Intending applicants should have a good undergraduate degree, or Masters, in geography, archaeology, history, architectural history or history of science and will need to satisfy AHRC eligibility requirements. Ideally, you will have experience of relevant research methods (advanced research training is a required element of the studentship). Applicants should submit: a two-page curriculum vitae, with a brief letter outlining your qualification for the studentship; a sample of scholarly writing such as a coursework essay or thesis chapter; and the names and contact details of two academic referees.

These should be sent to: Fraser MacDonald, Institute of Geography, Drummond Street, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH8 9XP (fraser.macdonald@ed.ac.uk) no later than 12 June 2013.

Interviews, which will be held in Edinburgh, are scheduled to take place on the afternoon of 27 June 2013. For further information regarding the studentship, please contact Fraser MacDonald (fraser.macdonald@ed.ac.uk ) / 0131 650 2293.

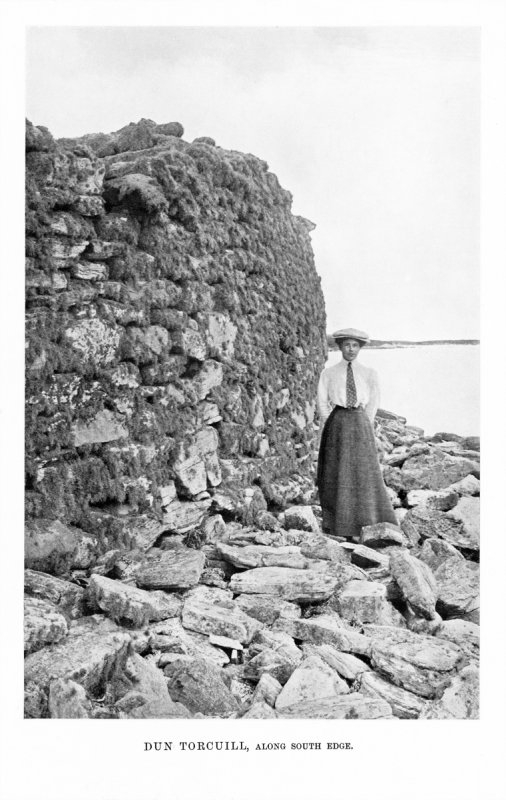

It was more lightly encrusted when the antiquarian Erskine Beveridge (1851-1920) visited in the early twentieth century. This is his photo of the site.

It was more lightly encrusted when the antiquarian Erskine Beveridge (1851-1920) visited in the early twentieth century. This is his photo of the site.