I came across a small haul of gold yesterday. One of my hawk-eyed PhD students, Ben Garlick, spotted some material in the archives of the Scottish Ornithologists Club belonging to Frederick S. Beveridge – a son of the Fife archaeologist and industrialist Erskine Beveridge.

I am slowly trying to piece together the life and work of this family from various archival fragments and from the ruins of their Hebridean residence on the island of Vallay, off North Uist.

For such a notable family – both wealthy and connected – it is amazing how few traces have survived. All of this makes the collection of bird notes by the young Fred particularly interesting.

Fred was inducted by his father in to the rituals of fieldwork: careful observation, recording, collection and analysis. Where Erskine Beveridge applied these techniques to the vestiges of antiquity, Fred and his brothers – George and David – put them to work in the service of ornithology.

None of them had an easy life. David died of dysentery at Gallipoli. George, forbidden to marry the love of his life, descended into alcoholism and eventually drowned while crossing the ford back to Vallay.

Fred steered the family linen business into liquidation, married unhappily and died on the birthday of his only daughter.

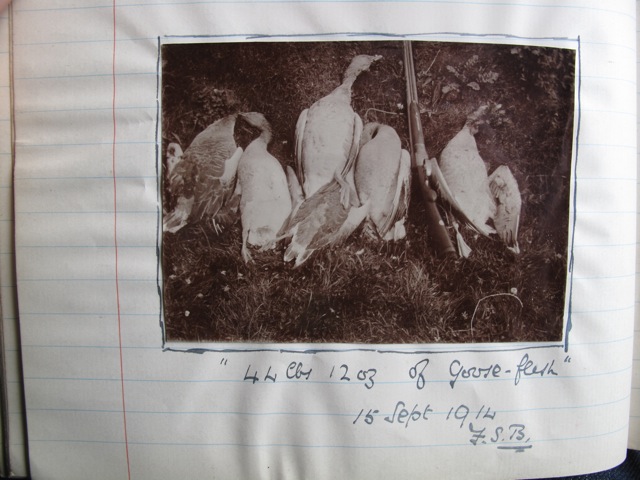

His birding notes in the SOC archive date to the time when the family fortunes were more buoyant; the game was certainly plentiful, at least on this evidence from Vallay.

Fred’s early observations on the birds of North Uist were eventually collected together for a scholarly paper in The Scottish Naturalist, a paragraph of which I quoted in my doctoral thesis:

The inhabitants of North Uist, when you know them, are a most agreeable people who have helped me in every possible way by observing new arrivals or rarities. I find but one fault of any magnitude, and that is a great passion for collecting birds’ eggs during the nesting season. During the early summer their women folk scour the foreshore in veritable hosts – they seem countless; […] they wander further and further afield, to return at dusk laden, not with cockles but with hundreds of wild birds’ eggs. No wonder that this trait does not appeal to one, but rather kindles in the onlooker the same spirit as that shown by our bovine friend at the sight of the proverbial red rag.

The local context to Fred’s complaint – though he might have felt it inappropriate for the pages of The Scottish Naturalist – was that land was in short supply and such eggs were a basic part of human nutrition. Within two years, impoverished islanders would threaten a land raid on the Beveridge estate.

Amongst the papers in the SOC, I found a letter from Fred to his father enclosing offprints of this article. It seems as if Erskine Beveridge might have been thinking about updating his own monograph North Uist: its archaeology and topography, with notes about the early history of the Outer Hebrides. Perhaps Fred’s paper could have been included in this as an addendum? In any case, Fred asks that should his bird article be reproduced then the above paragraph should be omitted – ‘more of a safety valve than anything else’. Interesting.

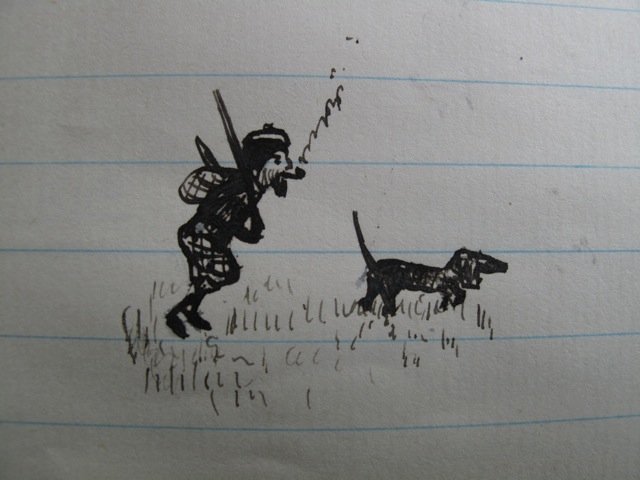

Also included in Fred’s notes are some curious little doodles and sketches. Take this one from 4th September 1915. Is this a sketch of his father? If it is a self-portrait, that is an impressive beard for a 19 year-old.

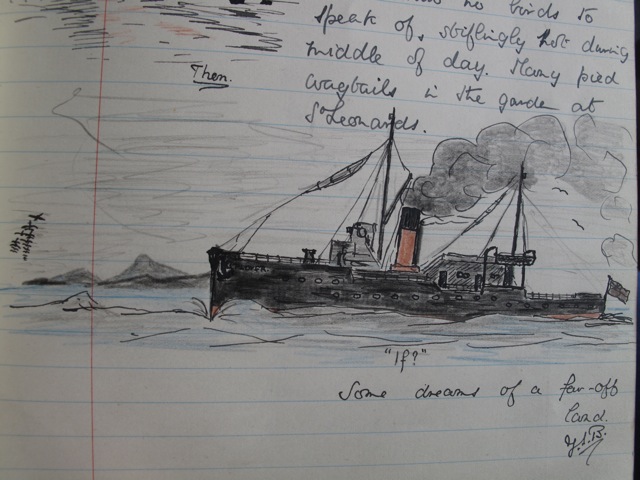

Or how about this sketch entitled “If” with the line ‘some dreams of a far-off land’?

The profile of hills looks like Eaval from Grimsay. The boat is called the Plover. Does anyone know any more detail about this vessel?

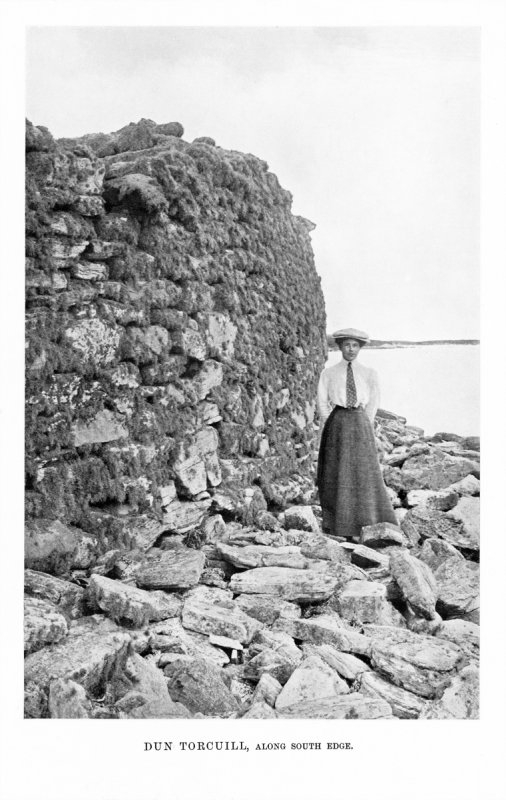

It was more lightly encrusted when the antiquarian Erskine Beveridge (1851-1920) visited in the early twentieth century. This is his photo of the site.

It was more lightly encrusted when the antiquarian Erskine Beveridge (1851-1920) visited in the early twentieth century. This is his photo of the site.