Levenhall Links is one of my favourite places, a small slice of the wild where Edinburgh spills into East Lothian. I escape here to watch the birds from an earlier age, when agriculture still found a place for lapwings and skylarks, curlews and meadow pipits.

Sitting behind the damp concrete wall of the bird hide, I lift my binoculars to scan the shallows for waders and ducks. On each visit they are alternately abundant and absent. The pleasure of anticipation is a little like that offered by a good second-hand bookshop: you never know what you’re going to get. Today, mostly oystercatchers.

Levenhall is a great place for a telescope. Wait … godwits! Are they bar-tailed or black-tailed? I’m definitely going to need the ‘scope for that.

Tilting the glass up from the waders, I follow a ship on the Firth of Forth and admire the outline of East Lomond rising above Glenrothes. There is a depth of field here.

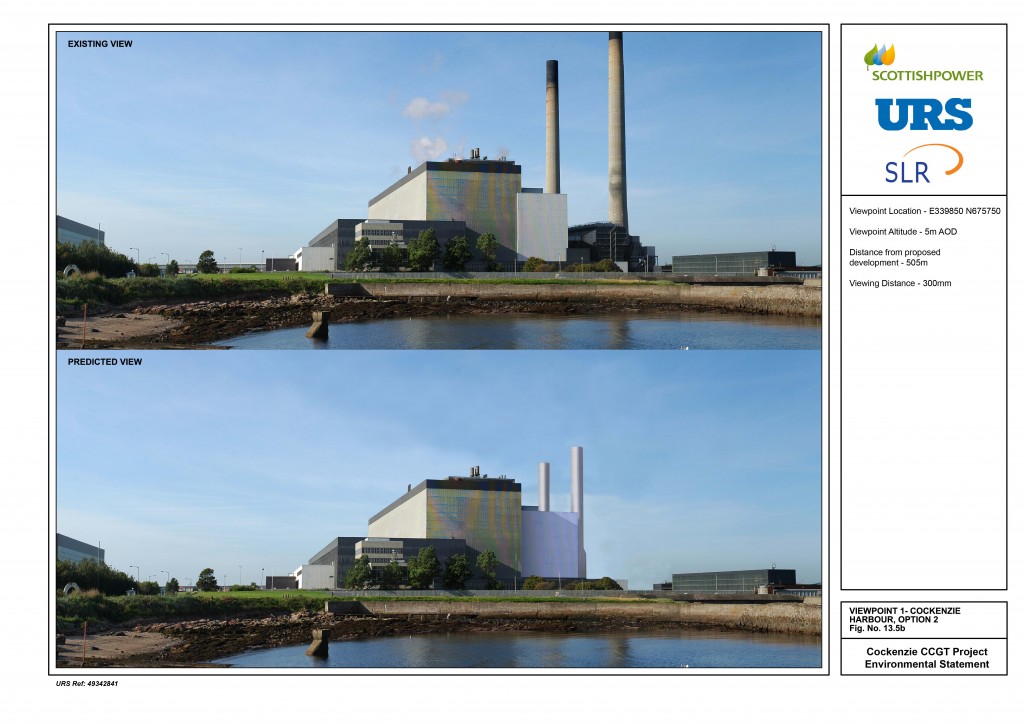

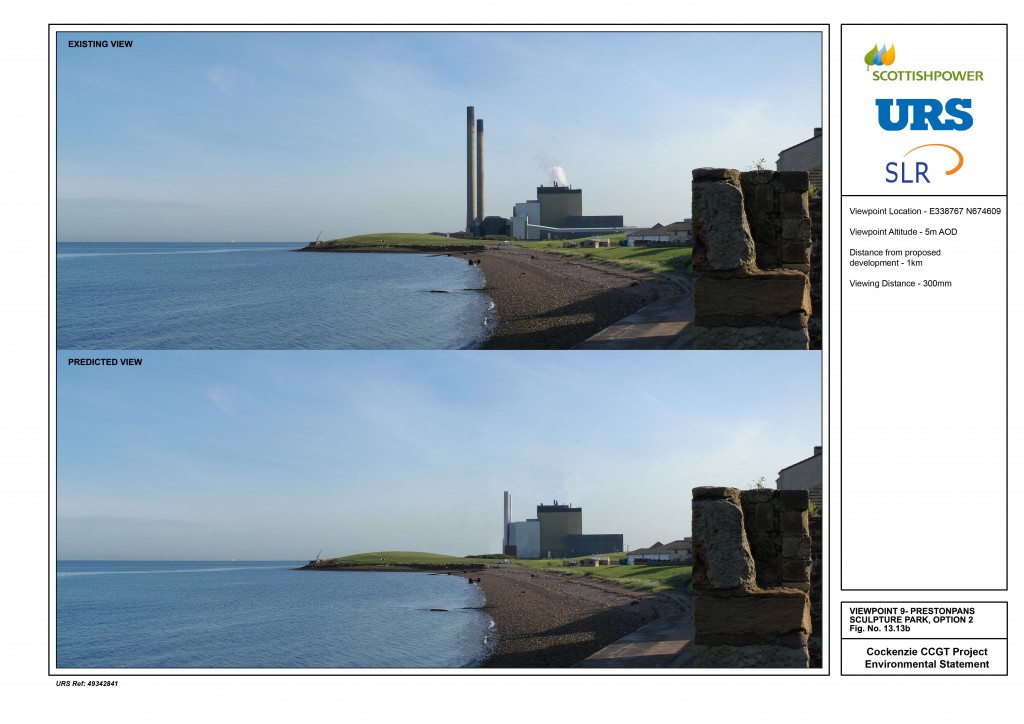

For all its apparent naturalness, there is nothing wild about Levenhall Links. The site is dominated by – and has its origins in – the imposing hulk of Cockenzie Power Station, the ash from which has been landscaped to create ‘wader scrapes’ for post-industrial godwits and their kin.

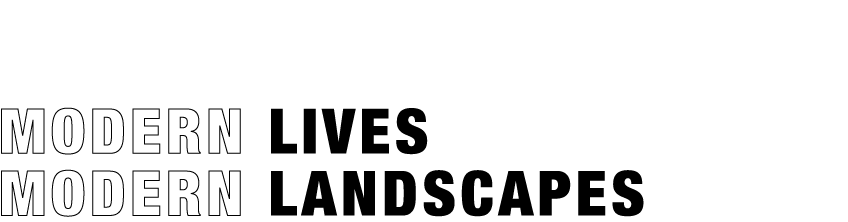

I love Cockenzie Power Station. It is hard not to be moved by what is reputed to be Britain’s least efficient coal-burning behemoth. Unfortunately the EU doesn’t feel quite the same way which is why it is being decommissioned next year. Whether it will also be demolished is as yet unclear.

Part of my fondness is architectural. Few towns are so dominated by a single modernist building as Cockenzie, which carries itself like a mediaeval cathedral towering over its hinterland. To lose it is to mark the end of an era – the dissolution of the carbon monasteries.

Modernism in Scotland seldom had such scale to work with and, in 1959, the architectural firm of Sir Robert Matthew did not waste the opportunity. It is a shame then that the building has fewer advocates than others from the same design partnership – most famously, the Royal Festival Hall on London’s South Bank and Edinburgh’s Royal Commonwealth Pool.

Located on the edge of the Midlothian coalfield, Cockenzie guzzled coal by the trainload which came snaking down the rails from the new superpits at Monktonhall and Bilston Glen.

Watching the godwits (bar-tailed, but you always have to check), I can’t help thinking of the late Professor Neil Smith – Marxist geographer, spatial theorist and also, apparently, a keen birdwatcher. His untimely death last month deprived geography of one its most lively minds (my colleague Tom Slater and Don Mitchell have both written fine tributes).

Smith’s work on the ‘production of nature’ shaped my early academic interest – the idea that nature is the outcome of social processes, not the other way round; that nature is, in a sense, congealed human labour.

The godwits preening on the pulverized fuel ash are on a substrate whose provenance lies in the labouring communities – not only in Cockenzie but also in mining communities across the Lothians.

A few miles south at the Monktonhall Colliery, the mine shaft was sunk over 900 metres – a inverted Munro’s depth – into the Jurassic past. Thousands of workers poured daily into this meticulously engineered abyss, capped with a winding gear that was itself encased in pulse-quickening Brutalist architecture.

These superpits were the pride of Scottish labour, at least until Thatcher’s henchmen at the National Coal Board, Ian MacGregor and Albert Wheeler, took revenge on an entire industry for the miners strike of 1984-1985.

Monktonhall had a reputation for militancy; many of its workers came from Neil Smith’s home town of Dalkeith.

All these material histories – of dirty, skilled and risky work; of solidarity and community – lie dormant in the mud at Levenhall, in the mountains that the miners moved, in the spoils of these now privatized utilities.

The aerial architecture of Monktonhall lasted just a few months into the era of New Labour but the site is still there, a dispiriting wasteland of new birch framed by mature ash avenues along the colliery bund. It is exceptionally quiet.

At least Monktonhall looks set to resist ‘amenity’ use. There is no getting round the fact that the ruins of coal-powered modernism aren’t pretty even after thirty years.

It is doubtless a good thing that Levenhall has been designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest. But I worry that the modern guise of nature-as-biodiversity is apt to obscure the ‘storyable’ properties of nature – of landscape as an archive of labouring histories.

In Neil Smith’s classic first book, Uneven Development, he observed that when the

“immediate appearance of nature is placed in historical context, the development of the material landscape presents itself as a process of the production of nature. The differentiated results of this production of nature are the material symptoms of uneven development.”

I know that this is not the usual stuff of contemporary nature writing, but perhaps it could be? Such natural histories might yield more politically productive accounts of the corresponding labour of humans and godwits.