Dealing with plagiarism is one of my least favourite aspects of academic life. Today’s case, however, is much more fun. And as it doesn’t concern any of my own students, it involves no additional admin. That’s already a win.

Yesterday I came across a sentence, that I once wrote in a paper for the Journal of Historical Geography, attributed to somebody else in the Guardian. To be honest, my surprise was not that someone had lifted my expression than that they had actually read my obscure paper about Rockall in JHG. I’ll take all the readers I can get.

The purported author of the sentence is Nick Hancock – a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society – who is going to live on Rockall for over two months in 2013 (plenty of time, one might think, to reflect on appropriate attribution).

Hancock is an ‘adventurer’ – or, when he’s not wearing a dayglo drysuit, an Edinburgh property surveyor – who is aiming to break the record for the longest occupation of this unwelcoming rock. As Hancock intends to be there for 60 days, living in what looks like a yellow septic tank lashed to the rock, I guess the obvious question is: why?

Rockall Solo is rather hazy on this, aside from a bid to raise money for the forces charity Help for Heroes which, Nick tells us, “does not seek to criticise or be political” but rather to simply support “those wounded in the service of our country since 9/11”. Founding patron: Jeremy Clarkson.

This theme of heroism takes us back to another rationale as articulated in my purloined sentence (from MacDonald, 2005: 632), now oddly turned into a tagline on Nick’s personal website:

“To have visited Rockall was the epitome of heroism and reflected well on the bravery and moral character of the traveller”

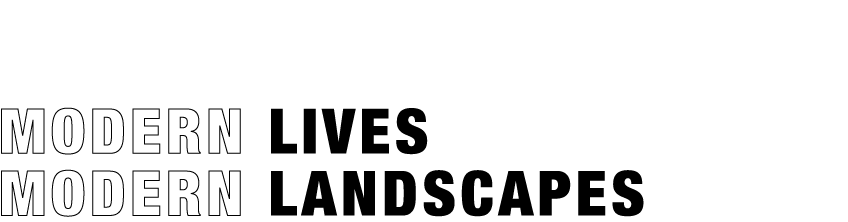

A painting from Rev. W. Spotswood Green, Narrative of the cruise introducing notes of Rockall Island and Bank, Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy 31, 3 (1896) 39-97, p. 46.

And here is the nub of it. In my paper (here: pdf 0.4mb) , I detail the slow emergence of a scientific professionalism that sought to distance science from mere thrill-seeking. At the same time, however, I argued that scientific accounts of Rockall were interesting in that they showed how science still retained the influence of the sublime – a bourgeois male aesthetic that celebrated heroism.

In the original paper, I was not trying to say that Rockall’s early explorers were a cut above the rest (splendid chaps – all of them). Rather, I meant that inside the paternalistic and imperial values of Victorian society, a landing on Rockall was to enact the perceived virtues of manly science.

In short: it was an argument about class and gender in the making of scientific knowledge; it’s definitely not an endorsement – not then, and not now.

If all of this sounds a bit grumpy, this is less about missing footnotes than about a wider complaint I have about the modern expeditionary culture that is shared among many of the non-academic members of the Royal Geographical Society. Many favour old-fashioned ‘discovery’: the search for geographical knowledge providing the scientific legitimacy for getting there first or staying there longest (for which read: secure the territorial claim).

The British annexation in 1955: Corporal A. A. Fraser watches First Lieutenant Commander Desmond P. D. Scott hoist the Union Flag on 18th September

And to be honest, there isn’t much discovery on Rockall Solo. The scientific rationale is, at best, wafer thin.

It was always thus. When naturalist James Fisher helped the British state annex Rockall in 1955 he used science to authorize a brazen geopolitical claim, all so that Britain could test its shiny new nuclear missiles over the Atlantic.

British Prime Minister Sir Anthony Eden, who that same year was to be found bombing his way through the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya, could be afforded this small advance amid a worldwide imperial retreat.

As I established in the paper, Rockall was the last ever territorial extension of the British Empire. All 83 feet of it.

This leaves Nick Hancock FRGS as just one of a long line of British occupiers – James Fisher, Andy Strangeway, Tom McClean – bearing the Union Jack and asserting the values of military heroism.

I don’t really mind the odd moment of bibliographic forgetfulness. But I find it much harder to overlook the pith-helmeted patriotism. After all, if the British claim to Rockall is so well founded, surely the rituals of discovery – settlement, flag-waving – are all a bit beside the point? Just ask the wildlife.

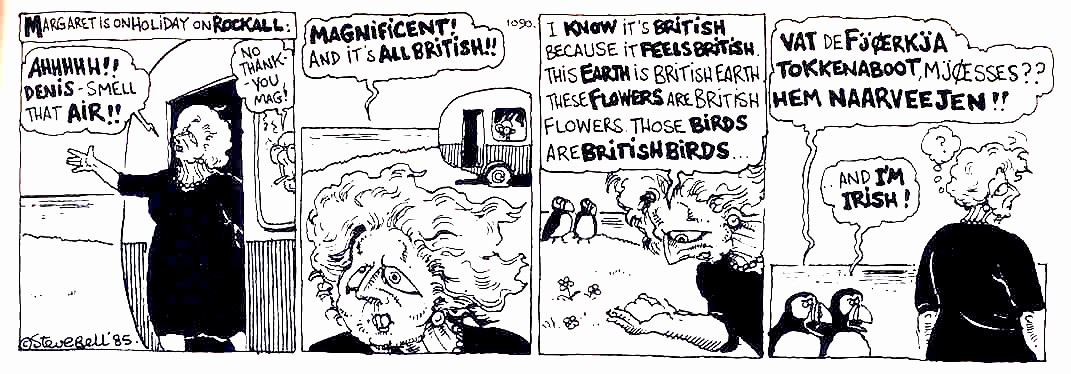

© Steve Bell If… 1985 The Guardian