I have a bit of past form for being churlish about all the attention devoted to St Kilda. Last week my persistent grumpiness was put to the test by visiting the archipelago for the first time, accompanied by students on our annual Edinburgh University human geography field class.

It is hard not to be moved by the grandeur. Such vertiginous heights – ‘steep frowning glories’ as Lord Byron might have called them – which are all the more impressive when given occasional perspective given by the tiny spec of an old fowling bothy. No photograph can really convey this scale and it is fair to say that I haven’t seen anything quite like it.

The built environment might have been equally striking had countless images of this abandoned village not already been intimately known to me since childhood.

The built environment might have been equally striking had countless images of this abandoned village not already been intimately known to me since childhood.

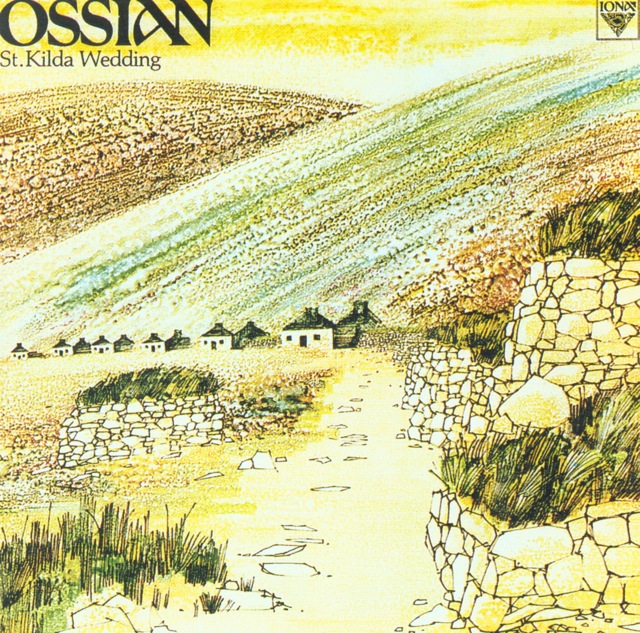

When I was eight years old, my brother bought an LP by Scottish folk pioneers Ossian. Entitled ‘St Kilda Wedding’, the cover showed a landscape rendered in pen and wax crayon. This evocative image, and the lovely reel from which the album draws its title, had me hooked – though it took me another twenty years to make my own contribution (pdf 0.5mb) to the story.

Maybe it was this longstanding familiarity that left me relatively unmoved by Village Bay. The curation in the village museum didn’t help matters. I think its emphasis on the difference of St Kilda compared to other Hebridean outliers is relentless and misplaced.

For instance, the charge of the islanders’ ‘extremism’ in religious matters is largely unwarranted, at least in comparison with other islands. It comes in part from the gawping ignorance of Glasgow Herald journalist Robert Connell in the 1880s and, subsequently, via uncritical accounts by Tom Steel and Charles Maclean.

I was further irked that the story of St Kilda basically stops with the evacuation in 1930, as if the later occupation by the military doesn’t quite count as a legitimate part of island history. A throwaway line about the Ministry of Defence being a partner in current management glosses over the remarkable Cold War history of the island.

Maybe the fact that this was the tracking station for the world’s first nuclear missile unsettles the wilderness ideal? How can such strategic centrality be reconciled with the island-on-the-edge-of-the-world framing?

My interests are admittedly rather niche but I found the signs of military occupation by far the most interesting aspect of St Kilda. Operation Hardrock, which saw the development of the radar tracking station in 1957, more than made its mark. And those involved in its construction left their own inscriptions.

All archaeologists love the discovery of a coin as a dating device. And doubtless this was in the mind of whichever workman placed a newly minted half penny in the wet concrete road – date side up, naturally. (Thanks to Kevin Grant, NTS archaeologist for pointing it out).

Other traces are less explicit but no less interesting: whose quiff was tamed by this black comb, found half way up Mullach Mòr?

A cement patch provides an enduring memorial.

And then there are inscriptions on a landscape scale: the origin of the materials for Operation Hardrock will not likely be forgotten any time soon. A quarry this size is hard to overlook.

All of this is fascinating but it is not the St Kilda we know. That story is fixated with a tragedy in which innocent pre-moderns are taken in by villainous missionaries. As with many founding myths of nationhood, it is a colourful lament for a golden age that is poorly anchored in the available evidence.

Meanwhile, the evidence for other lives and other landscapes remains carefully cropped out of our photos of Village Bay.