Harvard’s new RoboBee: a new step towards more sophisticated bio-mimicry and the likelihood of military applications on an analog insect body.

Harvard’s new RoboBee: a new step towards more sophisticated bio-mimicry and the likelihood of military applications on an analog insect body.

Yes, I realise that this epigraph is over the top. But I also think that the passing of Cockenzie Power Station, at least in its current incarnation, deserves further tribute, even one that falls short of outright regret.

I have previously extolled the architectural virtues of Cockenzie in other writing on this site and in The Guardian. But when I was finally offered a guided tour of one of my favourite buildings – thanks Scottish Power – I couldn’t help but brace for disappointment.

It didn’t disappoint.

Wow. Just wow. The scale is impossible to capture in photographs or, at any rate, in my photographs. You’ll find markedly better portraits of Cockenzie here by Alex Hewitt of The Scotsman.

But I’m posting these images in the hope that they convey some impression of this nationally significant building (Historic Scotland, unfortunately, doesn’t share this view).

Cockenzie’s closure has been on the cards since the advent of the European Large Combustion Plant Directive. This meant that Scottish Power had to either make Cockenzie compliant with the new emissions limits or ‘opt out’. They chose the latter, leaving only 20,000 hours of generation time which expired in March 2013.

In 2011, planning permission has been granted for a new CCGT plant but Scottish Power has not committed to such a station until the market conditions in the forthcoming Energy Bill become more apparent.

In the meantime, Cockenzie is subject to a long period of dismantlement. Technically speaking, this is not a case of demolition though with the impending demise of its iconic 500ft chimneys this does feel like ‘the shade of that which once was great’ is passing away.

Scottish Power’s sub-contractors, Brown and Mason, are now recycling all that they can from the site – much of it to be kept for spares in the sister plant at Longannet.

Auditing and re-sorting all this the equipment is an enormous task and is expected to take at least two years. Ultimately, the aim is to make the site ready for the CCGT plant if Scottish Power ever choose to make the investment.

Visiting the station in its current guise is rather odd. It is neither operational nor a ruin. It is not, in Walter Benjamin’s famous phrase, an object of ‘irresistable decay’. The site remains very active. Dismantlement turns out to be a very involved process – not altogether unlike construction.

I wish I could more closely document the unmaking of Cockenzie Power Station. Somewhere in the doorstop that is Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project, he introduces a collection of quotations on ‘demolition sites’ with the following directive: ‘sources for the teaching of construction’.

To prise apart this elaborate machine, built with the precision of a watchmaker but over 24 hectares, presents a rare opportunity to think about the origins and legacies of Scottish coal and its infrastructures.

Someone should really write about this.

The full text of Will Self’s Wreford Watson lecture on the psychogeography of Scotland has now been published, appropriately enough, in Scottish Geographical Journal. Readers familiar with this doughty organ will recognise this publication as something of a first, not least for being the sweariest contribution in its 130 year history. Admittedly the bar is quite low. Or high, depending on your view.

I will not need to convince you that the essay is a great read – you can see for yourself, thanks to SGJ and their publisher Taylor & Francis who have agreed to make it freely available. You can download the pdf here.

Alternatively, if you want to watch the lecture for yourself you can do so below – courtesy of the School of GeoSciences YouTube account.

Boston Dynamics has developed a new throwing arm, presumably so that Big Dog can play fetch with itself.

There is a significant event in the history of twentieth century Scotland that has, to my knowledge, never been properly acknowledged: the first successful transatlantic flight of an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle, which landed in South Uist in August 1998.

These days, of course, we call them ‘drones’. They are the means by which extra-judicial killings are increasingly being enacted, the Obama administration following George Bush in applying the technology to pick off a ‘kill list’ – entirely outside the scrutiny of courts or legislature.

The remarkable thing about the new drone warfare is how quickly it has become normalised. Well over 2000 people have been killed by US drone strikes in Pakistan alone, a sovereign country which is a close ally of the United States. And as my geography colleague Ian Shaw argues, the results of experience in overseas military operations are rapidly being applied at home, with all manner of domestic surveillance and control applications now awaiting us.

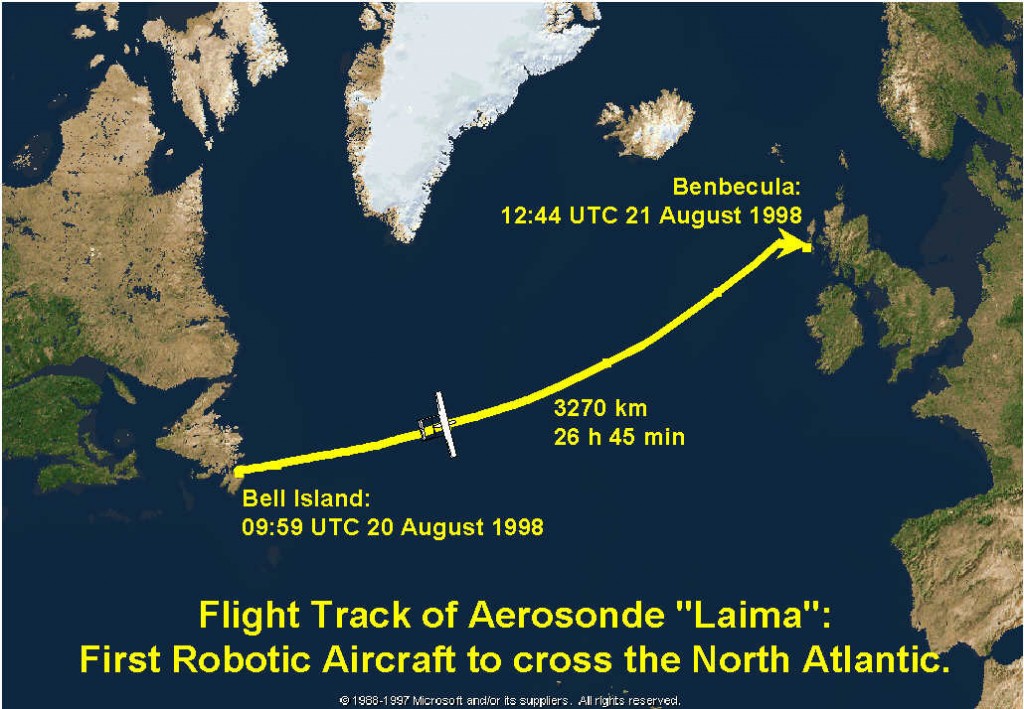

There is no direct kinship between the Predator drones at use in Pakistan and Yemen and the drone that landed at what is now the Qinetiq range in South Uist. But the event of the 21st August 1998 still represents a significant step – an important milestone of endurance – in the evolution of this wider technology.

What happened fifteen years ago still strikes me as extraordinary. Using less than three dollars’ worth of aviation fuel, a pilotless miniature robotic aircraft successfully completed a transatlantic flight, establishing records for the both the smallest aircraft and the first Unmanned Aerial Vehicle of any size to make such a journey.

Designed by Tad McGreer and the Washington-based Insitu Group, the Aerosonde ‘Laima’ (named after the Latvian goddess of good fortune) was launched from the roof of a family saloon car at Bell Island, Newfoundland.

It arrived in South Uist, about an hour late, taking 26 hours 45 minutes to complete the 3270km journey, being brought down to land on the machair without wheels and bearing only minor scratches.

Laima landed to very little fanfare in either the UK or the US. One person who did notice, however, was Jef Raskin, the one time colleague of Steve Jobs, who developed the original Apple Macintosh computer.

Raskin could see that the implications of Laima were far-reaching. The Aerosonde was cheap (under $10,000), lightweight (13 kg), undetectable, efficient (1300 miles per gallon), low-tech (made from variations on a lawnmower engine and a model aircraft) and yet sufficiently robust to potentially carry a nuclear device.

For Raskin, Laima’s flight to South Uist rendered the US Strategic Defence Initiative (the $200 billion dollar ‘Star Wars’ missile defence system) redundant at a stroke. If, for only a million dollars, he argued, one hundred such planes – some equipped with nuclear devices – could be launched against an American city, no existing or planned military hardware could possibly forewarn, far less forearm, against such an attack.

Fifteen years later, the fearful scenario that Raskin laid out – bearing more than a trace of post 9/11 anxiety – has happily not come to pass. But Raskin was surely right to see the strategic significance of drone warfare, the exact consequences of which are still hard to anticipate.

What we have learned from nuclear missiles – yes, these too were tested in the islands – is that there is no putting the genie back in the bottle. And unlike nuclear technology, the components of drones are rather more accessible – not only to state security services but also to those they seek to target.

T. McGeer and J. Vagners, ‘Historic crossing: an unmanned aircraft’s Atlantic flight’, GPS World 10.2 (1999), 24-30.

I’ve said it before and I’m saying it again: I love Cockenzie Power Station.

When I hit Portobello prom of a morning, I invariably give it a backward glance.

Later, when I’m crossing North Bridge over Waverley Station, I like to check that it is still there.

From this vantage point, the tourists are agog at the Scott Monument, the Nelson Monument, the Castle – even, heaven help us, at the Balmoral Hotel.

I’d flatten them all for Cockenzie Power Station.

Even from a proximity of ten miles, it looks monumental; the distant outline of Byres Hill gives it a picturesque frame.

If you have ever lived in Edinburgh you’ll likely know Cockenzie’s distinctive twin chimneys. But given that it is due to close at the end of March, now is probably a good time to give them some proper attention.

Cockenzie is closing because it positively belches carbon. That is, of course, what it was designed to do – turning coal into electricity – and it has done so productively since it opened in the midst of a turbulent May 1968.

I understand why these behemoths must die and I’m not going to attempt to defend their continued existence. Borne of good intent into an age of carbon innocence, they have served their purpose well.

Permissions are now in place to convert Cockenzie from coal to (more efficient) CCGT gas.

This is good news (sort of) for greenhouse gas emissions but bad news for one of the most distinctive landmarks on the east coast. These stately chimney stacks are set to be demolished in favour of two rather diminished replacements.

The aesthetic effect of this change is, as you can see from Scottish Power’s visualizations, fairly lamentable.

This is perhaps why I’ve been particularly attentive to Cockenzie in recent months – enjoying it, as it were, from every angle.

I can see that it doesn’t make sense to import coal from Russia now that our own industry has been destroyed or exhausted.

But the presence of Cockenzie Power Station in the landscape is one of the last monuments to a wider modernist project for the Forth that saw the development of Livingstone and Glenrothes, the Forth Road Bridge and sibling power stations at Longannet, Methil and Kincardine.

In Portobello, the outline of Cockenzie has a particular resonance given that it was the replacement to our own no less remarkable power station, opened by George V in 1923, and finally demolished in 1976.

It is doubtless too late to save the twin towers of Cockenzie. But it does seem symptomatic of a wider disregard of our modernist heritage as well, perhaps, as speaking to a more general discomfort with our having been modern in the first place.

Here is a video of the Scottish psychiatrist R. D. Laing, filmed at the height of his fame in 1973.

I’m not sure why I am posting this: it just seems somehow remarkable. It is an odd conversation; and more than a little disturbing.

Is it supposed to be funny? I don’t know. It is intriguing because on the surface it seems phony. And yet what is most troubling – regardless of the biographical veracity of the details – is its sheer excess of authenticity.

Laing’s short storytelling at the end feels of a piece with his earlier face-pulling: a matter of posturing, playing and pretending. It is pointless to dwell on whether the story is ‘true’ given that – for Lacan at least – it is in the most hysterical lies that we unwittingly articulate the truth.

The variety of user comments on the YouTube clip all seem entirely right: everything from ‘pointless, charlatan shite’ through to ‘an absolute genius – and for that we will never forgive him’.

Or, as one viewer said, ‘I think I’m in the weird part of YouTube again’.

There has been a bit of background chat in recent years about the correspondence between geography and poetry. A conference session was organised at the IBG in 2010. Last year, Royal Holloway inaugurated a new MA in Place, Environment, Writing with a lecture by Sir Andrew Motion.

One of the animating figures of this new programme is the geographer Tim Cresswell who has his own new collection of poetry out later this year.

And here in the parish of @EdinGeography, we hold our seminars under the mustachioed visage of poet and geographer James Wreford Watson – a doppelgänger of Bruce Forsyth – whose acclaimed landscape elegies in the 1950s were laced with an edge of genteel smut.

Much less attention, however, has been given to the geographer-poet, Harry Smart, who published three collections of work with Faber in the early 1990s – Pierrot (1991), Shoah (1993) and Fool’s Pardon (1995).

Fool’s Pardon, Faber, 1995

Admittedly, Smart is less of a geographer-poet than a poet who happens to have a PhD in geography. His thesis, submitted to the University of Aberdeen in 1984, was later published as a Routledge monograph – Criticism and public rationality: professional rigidity and the search for caring government (1991).

One suspects that geography was not, for Smart, a formative intellectual home; in any case, he left it behind sometime before the ‘cultural turn’.

Living in Aberdeen, and later in Montrose, Smart took some cultural turns all of his own, leaving academia to become an evangelical lay preacher, then a poet. Three collections with Faber can reasonably be called success.

After poetry, fiction: his political thriller set in 1960s Africa was titled Zaire (Dedalus Books, 1997), though the fact that the country of that name immediately declared itself as Democratic Republic of the Congo probably didn’t help sales.

In 2000, Smart enrolled in a Master of Fine Art at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art in Dundee where he undertook painting and photography – you can read some of his reflections on his art practice here.

Black Apple © Harry Smart

It’s fair to say that his visual art, like his writing, does not shy away from darker themes. His website – distinctly NSFW, as they say – is a fascinating labyrinth of essays, excerpts, poems, photos, art and erotica. Though it hasn’t been updated for many years, it is well worth a visit.

I was intrigued to discover some photographs in which the Montrose railway bridge – designed by the same architect as the ill-fated Tay Bridge – became a backdrop to some calendar shots. This is by no means the most surprising juxtaposition on the website.

The estuarine landscapes of Montrose and the east coast also appear in Smart’s poetry. The following poem, Praise, from Fool’s Pardon, is a particular favourite. A rendering of Scottish Calvinism and landscape, it takes the form of a modern doxology.

It has often come to mind when exploring the Firth of Forth in these dark January days.

Praise

Praise be to God, who pities wankers

and has mercy on miserable bastards.

Praise be to God, who pours out his blessing

on reactionary warheads and racists.

For he knows what he is doing;

the healthy have no need of a doctor,

the sinless have no need of forgiveness.

But, you say, They do not deserve it.

That is the point; that is the point.

When you try to wade across the estuary at low tide

but misjudge the distance, the currents, the soft ground

and are caught by the flood in deep schtuck,

then perhaps you will realise that God is to be praised

for delivering dickheads

from troubles they have made for themselves.

Praise be to God, who forgives sinners.

Let him who is without sin throw the first headline.

Let him who is without sin build the gallows,

prepare the noose, say farewell

to the convict with a kiss.

.

Dealing with plagiarism is one of my least favourite aspects of academic life. Today’s case, however, is much more fun. And as it doesn’t concern any of my own students, it involves no additional admin. That’s already a win.

Yesterday I came across a sentence, that I once wrote in a paper for the Journal of Historical Geography, attributed to somebody else in the Guardian. To be honest, my surprise was not that someone had lifted my expression than that they had actually read my obscure paper about Rockall in JHG. I’ll take all the readers I can get.

The purported author of the sentence is Nick Hancock – a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society – who is going to live on Rockall for over two months in 2013 (plenty of time, one might think, to reflect on appropriate attribution).

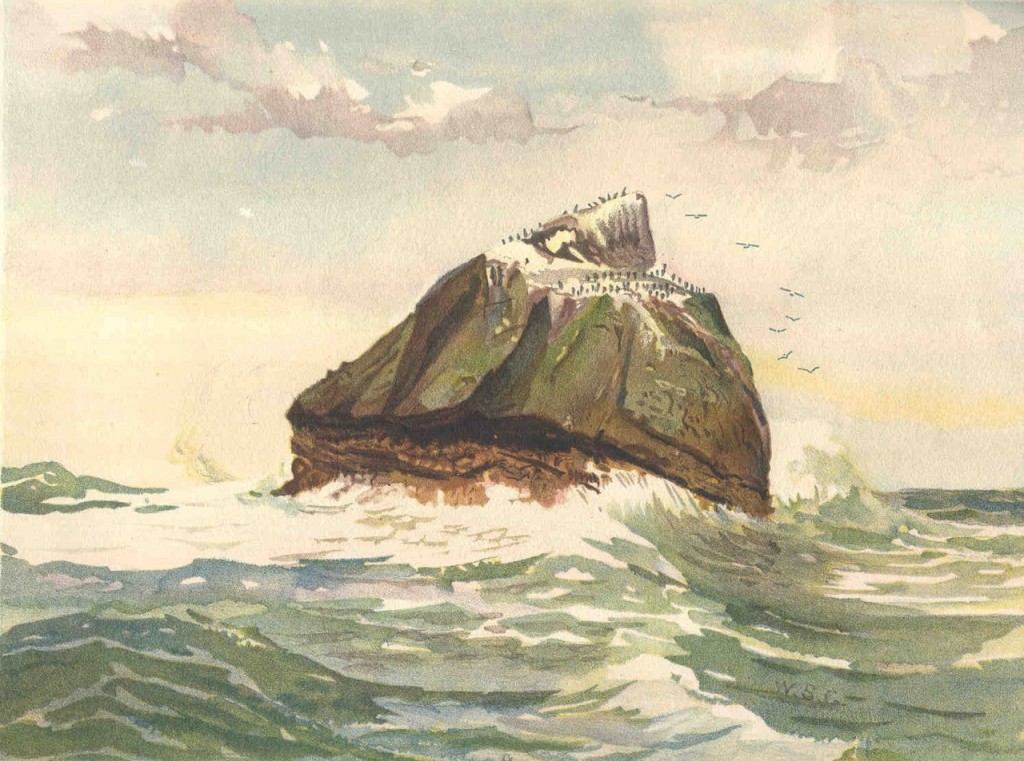

Hancock is an ‘adventurer’ – or, when he’s not wearing a dayglo drysuit, an Edinburgh property surveyor – who is aiming to break the record for the longest occupation of this unwelcoming rock. As Hancock intends to be there for 60 days, living in what looks like a yellow septic tank lashed to the rock, I guess the obvious question is: why?

Rockall Solo is rather hazy on this, aside from a bid to raise money for the forces charity Help for Heroes which, Nick tells us, “does not seek to criticise or be political” but rather to simply support “those wounded in the service of our country since 9/11”. Founding patron: Jeremy Clarkson.

This theme of heroism takes us back to another rationale as articulated in my purloined sentence (from MacDonald, 2005: 632), now oddly turned into a tagline on Nick’s personal website:

“To have visited Rockall was the epitome of heroism and reflected well on the bravery and moral character of the traveller”

A painting from Rev. W. Spotswood Green, Narrative of the cruise introducing notes of Rockall Island and Bank, Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy 31, 3 (1896) 39-97, p. 46.

And here is the nub of it. In my paper (here: pdf 0.4mb) , I detail the slow emergence of a scientific professionalism that sought to distance science from mere thrill-seeking. At the same time, however, I argued that scientific accounts of Rockall were interesting in that they showed how science still retained the influence of the sublime – a bourgeois male aesthetic that celebrated heroism.

In the original paper, I was not trying to say that Rockall’s early explorers were a cut above the rest (splendid chaps – all of them). Rather, I meant that inside the paternalistic and imperial values of Victorian society, a landing on Rockall was to enact the perceived virtues of manly science.

In short: it was an argument about class and gender in the making of scientific knowledge; it’s definitely not an endorsement – not then, and not now.

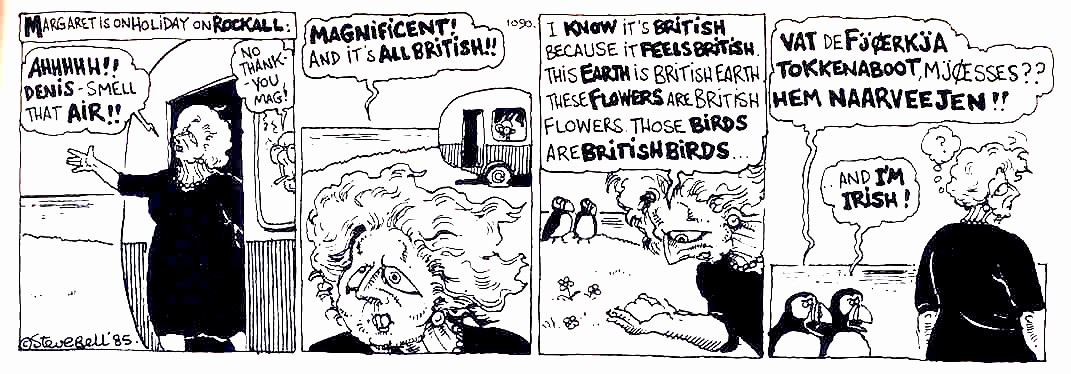

If all of this sounds a bit grumpy, this is less about missing footnotes than about a wider complaint I have about the modern expeditionary culture that is shared among many of the non-academic members of the Royal Geographical Society. Many favour old-fashioned ‘discovery’: the search for geographical knowledge providing the scientific legitimacy for getting there first or staying there longest (for which read: secure the territorial claim).

The British annexation in 1955: Corporal A. A. Fraser watches First Lieutenant Commander Desmond P. D. Scott hoist the Union Flag on 18th September

And to be honest, there isn’t much discovery on Rockall Solo. The scientific rationale is, at best, wafer thin.

It was always thus. When naturalist James Fisher helped the British state annex Rockall in 1955 he used science to authorize a brazen geopolitical claim, all so that Britain could test its shiny new nuclear missiles over the Atlantic.

British Prime Minister Sir Anthony Eden, who that same year was to be found bombing his way through the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya, could be afforded this small advance amid a worldwide imperial retreat.

As I established in the paper, Rockall was the last ever territorial extension of the British Empire. All 83 feet of it.

This leaves Nick Hancock FRGS as just one of a long line of British occupiers – James Fisher, Andy Strangeway, Tom McClean – bearing the Union Jack and asserting the values of military heroism.

I don’t really mind the odd moment of bibliographic forgetfulness. But I find it much harder to overlook the pith-helmeted patriotism. After all, if the British claim to Rockall is so well founded, surely the rituals of discovery – settlement, flag-waving – are all a bit beside the point? Just ask the wildlife.

© Steve Bell If… 1985 The Guardian

For all the contemporary interest in cultural landscape interpretation and conservation, there are plenty of sites that elude official attention. Many are just too awkward or too obscure.

Finlay Munro’s footprints at Torgyle, Glenmoriston is arguably one such: a set of footprints imprinted in the clay since the 1820s as a muddy testament to the religious truths proclaimed by an itinerant evangelical preacher.

The Footprints, from GNM Collins, Principal John Macleod D.D. (1951)

Finlay Munro was, by all accounts, a strange and charismatic figure. Born in Tain, he became famous for tramping the byways of the Highlands and islands preaching an evangelical gospel to anyone who would listen.

“The clergy were mad against him,” recalled Rev Alexander Maclean of North Uist, “and the ignorant and wild people dealt brutally with him in every place”.

And yet Munro had his followers – despite the disapproval of the ministers who resented this unkempt upstart distracting their own flocks.

In Lewis, an immense congregation gathered on the low hill of Muirneag where people often met for worship. Such were the multitudes gathered on the slopes, that Munro in his sermon addressed the hill itself: “Muirneag, Muirneag, it is you that may feel well pleased today with your new coat on” (a pun on the Gaelic name, ‘little pleasing one’).

In a short portrait of Munro, Free Church Principal John Macleod (1872–1948) quotes an old crofter friend of his – Archie Crawford – who, as a boy, had heard Munro preaching in his father’s barn. “He [Crawford] formed the opinion” writes Macleod with some understatement, “that there was something unsettled about him, and, indeed, that he was odd”.*

Though by no means unaccustomed to ridicule, Finlay Munro was subject to some particularly disruptive hecklers when preaching in Glenmoriston in 1827. That his tormentors were allegedly Roman Catholics from Glengarry surely adds to the currency of the tale.

Munro stood his ground. He told them that the very clay would testify to the truth of his words; that his footprints would endure – until his hearers met their judgment or, in some accounts, until the Day of Judgment.

And there they remain – an epistemic imprint. They are not, despite their protective cairn, very easy to locate. The most reliable means of finding the site is to use the OS grid reference – NH 311138. A map can be found here.

Such landscapes are invariably awkward for the appointed guardians of heritage. For one thing, they tend to commemorate or evoke traditions, values and stories that don’t readily translate into the secular world.

An unthreatening veneration of Celtic Christianity is all very well but who, in officialdom, wants to recall spiritual intensities, conversions, callings, judgments, liberties in prayer and convictions of sin?

And yet these aspects of Highland experience arguably occupy a large part of the oral tradition in the last two hundred years and they, in turn, find their expression in the storied landscape.

This sort of lore stirs us – but uneasily; it draws out our aversion to the uncanny. Nothing in modern Scotland is more familiar and more foreign than Calvinism. That’s why it is interesting.

Notes

*John Macleod, ‘A Highland Evangelist’ in GNM Collins, Principal John Macleod D.D., Free Church Publications Committee (Edinburgh, 1951).